Something about video games has always felt a little off to me. This uneasiness has had a tendency to manifest itself in my mind most readily in the moments of great self-doubt as a loss of motivation for continuing to play the title I am currently mainly focusing on, or more severely, a more overarching sentiment regarding all of gaming. I am certain that the same applies to everyone but the steps that follow this feeling can vary depending on the individual: an average non-questioning gamer will take a break or find the next dopamine hit, those interested in game design will try to identify the gaps in and brainstorm the possible improvements to the gameplay loop so as to maintain the player engagement, and when I am feeling particularly inspired, I would let my wild wander and contemplate how this phenomenon might be indicative of a greater underlying truth about life itself, hidden behind this manufactured entertainment device.

While the exploration of human motivation and its constituting elements one can glean using the available tools exceeds the limits of this essay, we can use the exercise of deconstructing one of the pioneering and the best examples of this (admittedly, far more limited and only somewhat analogous) model: Diablo.

Diablo (1997) streamlined the concept of mechanical role-playing game progression by distancing itself from the underlying D&D roots of the genre, shifting the focus straight to worshiping the progression of one’s character sheet and delivering more action-oriented combat by putting all the calculations in the backend. Diablo II (2000) improved on this formula in almost every respect and polished this experience to an almost perfect shine.

~

Revered by some for his extraordinary offensive and defensive capabilities, great flexibility and ease-of-play, loathed by others for his ubiquity and the potential for being a little too good at everything when leveraging certain elite items like the unique teleport-granting body armor rune word, the ‘Enigma’.

The premise sounds embarrassingly simple when attempting to explain it to someone who has never played it (or any games that borrowed from it): you have your isometric top-down view, you control your guy, click on little monsters over and over to move through levels, acquire better equipment and improve your skills, and most importantly, continue doing so long after you complete the game and see all its game assets. If we set aside the well-aging, digital-painting-like 2D visual design, the subtlety of the story that does not demand that you pay attention to pages of dialogue but rather lures you in with mysteries, and the high production value for the time, this seemingly quixotic dream of infinite repetition that stays engaging and fun can perhaps be broken down into design elements that would prove more illuminating of this title’s lasting impact.

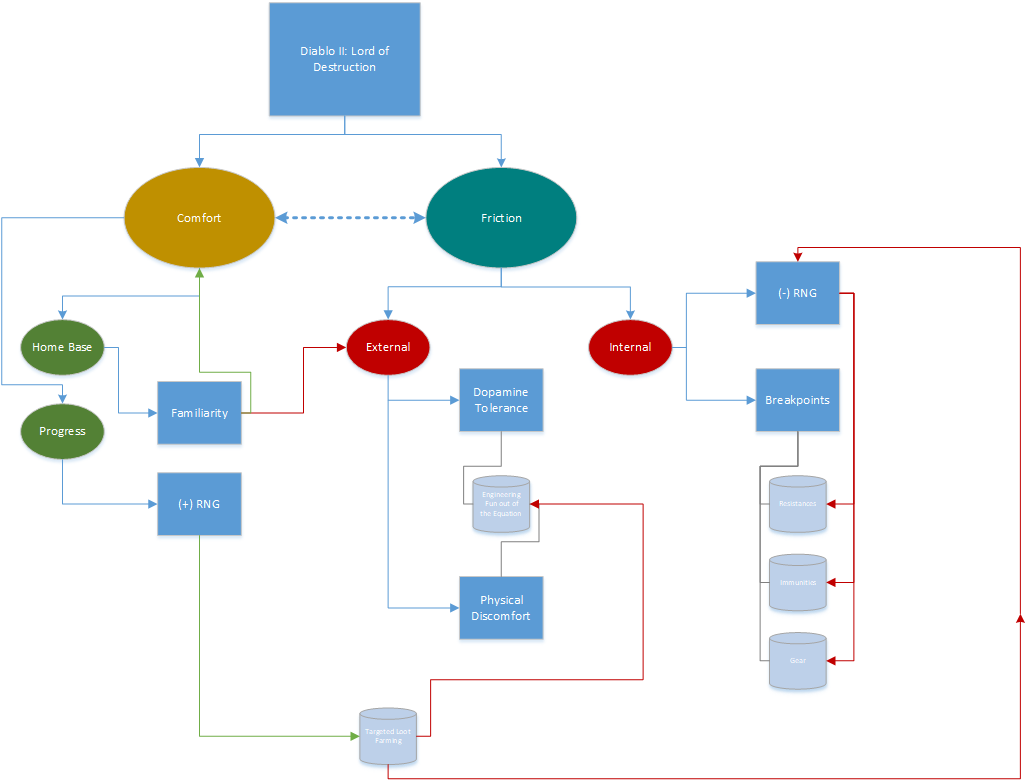

Comfort must be counterbalanced with friction in order to simulate the qualia we get from real-life achievements and our struggles which lead us towards them. Diablo leverages its role-playing backdrop to mechanistically lay bare the rules of the game — with monsters that have visible health pools, abilities and resistances, items which are described in a way that one can (given sufficient time, even fully) understand the intricate interplay of them and the character stats and skills — while at the same time, doing all those calculations for the player in a manner that is efficient, satisfying and visceral. Where tabletop D&D used the dice as an instrument for creating a simulacrum of entropy, giving weight to the stories and encounters they governed, Diablo supercharged this to tap into its more primal experiential roots of expectation and reward. And the final piece? Carefully tuning, i.e. balancing, the game to give sufficient pushback at all times and not allow the player to “break it” (involving a number of computationally interesting, psychologically perhaps less so, game design tweaks to the way the enemies and item (“loot”) tables correlate to the character progression at any given stage).

Whether intentionally or not, the resultant model parallels the “dopamine treadmill” that is thrust upon us from the day we are born and is essentially what we describe as motivation. By doing things that are immediately fun (click on stuff and watch the effect that we consider stimulating visual imagery), bolstered by the entropic unreliability of the reward cycle (represented by the positive and negative random number generator (RNG) in Diablo), we can reach a certain flow state, knowing we can expect good things (serotonin release) to come for comparably little investment except time. When contrasted with the non-virtual life where humans can have severe emotional or physical consequences for failing to reach the desired outcome in so many circumstances, it is easy to see why this model is appealing to the brain. This lasting appeal is further cemented through increasing familiarity with the game and Diablo’s “home base” to which one’s character returns between “farming” sessions (doing combat in certain areas or versus certain enemies to target certain item drops). This mental “hook” stimulates the dopamine receptors which “remember” the comforting aspects of the activity (receptor upregulation), thus resulting in an addictive loop where thinking about playing the game, or playing it expecting a desired reward, releases dopamine. While this cycle would naturally lead to tolerance after recognizing the pattern and starting to expect the reward (external), Diablo’s internally regulated tension can be maintained through several pathways which boil down to negative RNG effects (not getting the right loot to complete character builds) and not having the skill or the knowledge to push past the game’s increasing difficulty (knowing how to build a character or one of its many diverse classes). Reaching these “breakpoints” provide a long-term goal that is acutely felt through increasing friction in the game. An interesting side effect of this finely tuned game balance is that targeted loot farming in the most efficient way, while alluring players with the prospects of improving more rapidly, can get overly familiar and thus, boring, therefore working as a deterrent to engineering the fun out of the game in the most obvious way – by showing it is not the ultimate driver of fun in Diablo as it would lead to possible burnout before getting all the item drops that one is farming for.

One thing to note in this analysis: I have spent thousands of hours on Diablo games (1, 2 and 3) but mostly in single-player. The multiplayer mode can bootstrap a good part of the farming dullness via its trading system, offering a system akin to an MMO like World of Warcraft (2004). Inevitably, the dopamine tolerance sets in just the same, if quicker. That said, the MMORPG genre can offer a unique aspect not found in other games, which triggers the amygdala to solidify the value of experiences by virtue of them being shared. Being a social species, this only makes sense for humans, and warrants further exploration.

To circle back on the uneasy feeling this author gets while playing a game, I believe the key to answering this can be found – at least for the time being – in identifying where “the wheels start to fall off” in Diablo’s gameplay loop. Under ideal circumstances, an advanced iteration of Diablo could evolve by addressing and patching up these gaps. In terms of the game itself, this could mean tweaking the class or item balance or a drip feed of new, high-quality content or gameplay systems (notably, addressing the repetitiveness of targeted farming of a missing piece to complete a build). However, I cannot help but feel that while this could result in a better Diablo-like game (which in and of itself is a feat that I hope Lost Ark or Diablo II: Resurrected will accomplish), the philosophical dream of fixing every gap in the gameplay loop of one “perfectly designed” game has to be utopian. The reason a fun activity gets tedious over time is not only tied to the game itself – even the most wondrous sights and sounds, most compelling experiences and intricate systems, they are only “fresh” in our minds for a definite amount of time. What this obvious and overly generalizing argument exposes should one go on a tangent is that even when these experiences are still novel, there is still the aspect of external friction to playing a game that is often neglected in these considerations.

Gaming is a lot like bodybuilding and vice versa; but while many aspiring bodybuilders, myself included, find this analogy insightful, given enough time and practice it becomes painfully obvious why it is not a one-to-one analogy. The core tenets of bodybuilding are known to all: work out and eat a certain way to reach the body fat percentage and muscle mass comprising the goal physique. An inexperienced bodybuilder however will fail to recognize that their body is a living thing that they do not fully control at a molecular level. Simply eating the healthier foods to heart’s content and doing some exercises is not enough, one need to create a caloric deficit/surplus which impacts one’s satiety, mood, behavior, sleep, wellbeing, and to gain or preserve muscle one has to push past their limits, which often means accepting some form of temporary or prolonged suffering (soreness). These adverse effects of manipulating the body are greatly compounded by hormonal adaptation through lowered testosterone, increased cortisol, leptin resistance etc. An idealist or a rookie will dream of changing everything as if life were a game where the player can suffer through all kinds of trials without flinching. The reality is that not even a video game works like that, intrinsically or extrinsically. We play games to have fun, whether it be simple forms of fun like a pure action game or something more complex like Diablo that tickles the idea of the slow-burner type of satisfaction. Yet every game only mimics the circuitry that our body uses for gamifying life, otherwise we would not have a reason to do anything (Maslow’s hierarchy illustrates this well). Our physiological needs are funnelled into our psychological needs for exploration, self-actualization, belonging. I will posit that the reason Diablo is fun is that it replaces these (at least partly) by smuggling itself into our brain as a pseudo-need, a pseudo-model. It fails extrinsically when the player starts to feel like their time is not appreciated, or that they are neglecting the selves seated at their computer desk, reflecting on their physical discomfort, hunger (or obesity due to snacking), lack of sleep or mental exhaustion and the time wasting nature of an unfruitful, prolonged session of Secret Cow Level farming. Games can complement one’s life, but never perfectly. You cannot build your body by hoping to exploit the principles of bodybuilding to an extreme degree (binging and skipping days of eating randomly, overtraining). Similarly, you cannot expect to build the wellbeing of your mind through Diablo, however great of a game it is, by infinitely exploiting its potential, as the one experiencing that is also living inside a “game” of interconnected hormonal systems that push back or deteriorate through undesirable adaptations such as dopamine tolerance, obesity, muscle wasting.

Ultimately, as every game (virtual or even actual sports) stems from the game of life, which is inherently flawed, so is every dream of a perfect game, a utopian dream.